Howdy, i searched the 'net already for a bit and could not find information on this.

I see that on a site like this: https://framebuildersupply.com/collections/main-tubes

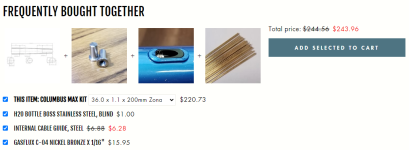

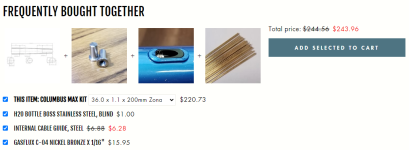

I could buy the materials to make a basic hardtail chromoly MTB frame for somewhere around $300. Since i don't know anything about frame-building, i'm going to add a buffer to that for dropouts, cable guides, etc and call it $400.

Also there exist complete kits.

Paintwise, what am i looking at? $100 of paint/clear coat?

I'm estimating a total cost of approximately $500 if i use mid grade chromoly parts all around.

How close am i to reality?

I see that on a site like this: https://framebuildersupply.com/collections/main-tubes

I could buy the materials to make a basic hardtail chromoly MTB frame for somewhere around $300. Since i don't know anything about frame-building, i'm going to add a buffer to that for dropouts, cable guides, etc and call it $400.

Also there exist complete kits.

Paintwise, what am i looking at? $100 of paint/clear coat?

I'm estimating a total cost of approximately $500 if i use mid grade chromoly parts all around.

How close am i to reality?